From 2004 until 2018, Dr Marie Cassidy’s image was synonymous with breaking news of high-profile murder cases. From gangland shootings and stabbings, to drug deaths, road traffic accidents and suicides, this former State Pathologist has performed thousands of post-mortems and dealt with hundreds of murders. But two years ago she retired suddenly and moved from Dublin to London, with her husband. A self-confessed workaholic and introvert she set about getting fit, attempted to perfect the art of small talk and – she wrote a book.

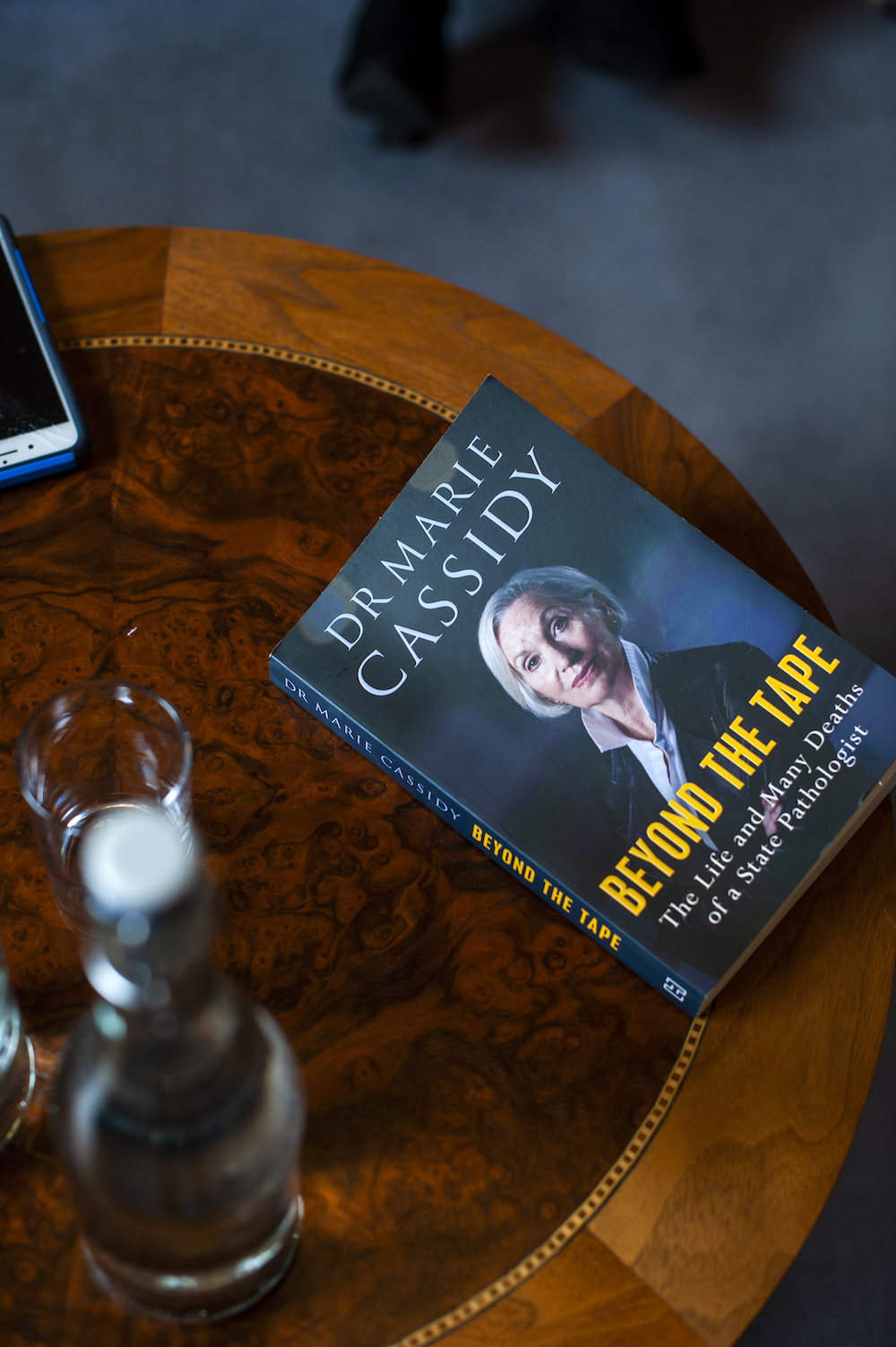

Beyond the Tape is a unique behind- the-scenes journey into the mysteries of unexplained and sudden death. With the scalpel-like precision and calm authority of her trade, Marie shares her remarkable personal journey from working-class Scotland into the world of forensic pathology, describing in candid detail the intricate processes central to solving modern crime. A fascinating woman, and not at all what you would expect, we quiz her on her life and her many deaths.

You say the Irish are obsessed with death. Why so, Dr Cassidy?

I think it’s because Ireland is still small. There’s not six degrees of separation between you and someone who has been found dead. You always know somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody, and so it becomes a death you need to know about, because it’s almost “family”. There’s always intrigue.

There’s a lot of intrigue in your job…

Even I’m intrigued by my job! I’m always trying to tell people how interesting it is whether they want to hear it or not! But I don’t think my job makes me worry about death and dying more… [thinking]… I could walk out of here today and get run over by a bus. Things happen.

I stayed up late last night reading your book, engrossed. Then I got spooked! Seeing what you have seen, did you want to, when your children were younger, wrap them up in cotton wool and never let them out?

I was ambivalent about it. I knew all the bad things that were out there so I did try to warn them, but at the same time they needed to work it out for themselves. I think they were happier when I was away working because I wasn’t there going, “Don’t do this” or “Don’t go there”. When I was home I was much stricter.

And you were away a lot. Such devotion to the job was required that you spent literally years on call. Your colleagues, you say, became your friends, your husband, a single parent. For over three decades you ate, slept and breathed death.

I did. I had so little time at home, and any time I did have, I spent with the kids. My daughter used to always say, “Mum, you’ve got no friends!” and was like, “I know!” I didn’t have any time to have friends.

In the 13 years you worked in Glasgow you say you did some 5,000 postmortems. How many in your 14 years did you do here?

A good few thousand anyway.

And in those 14 years did you see an increase in gruesome murders?

The strange thing is, the murder rate seems to stay static – in Scotland as well, actually. But what we’re seeing is there is probably more violent crime out there, but with the advances in medicine more people are being kept alive longer. So if back in the 80s you were stabbed in Glasgow by the time an ambulance got to you, bundled you in and got you to the hospital, chances are you would be dead. So crime overall may have gone up, but the cases that come to us, have not. In Ireland there has been a change in Irish society, in the last few years in particular, because the population has changed. So yes, we see a lot of the gangland stuff, but also there’s an influence from other countries which is influencing the violent acts committed.

I was telling my 10-year-old while walking to school this morning who I was coming to interview. And he said, “that’s a very sad job”. Is it? Is what you see sad?

I think how it affects the families left behind, is sad. Luckily when I’m doing my bit, I don’t see the effect it’s had until later down the line, until we get to court. And it’s at that point that it gets sad. And every family reacts differently. Often a tragic death breaks a family. Often at inquests you may see families so torn apart they can’t even sit together. It’s like a pandemic, they’re sitting more than 2 metres apart! I just see a body, it’s a tragic thing, but it’s the repercussions, the aftershocks, which are so sad.

You say that more often than not, murder tends to happen in the lower socioeconomic bracket. And that if the jury visited the home, and often saw the state of the homes some people live in, that they may have more compassion for the accused.

For years I have spent my life wandering through homes, no, not homes, they’re never homes, hovels, and often there’s not even a bed, just a mattress on a floor. And I have often thought, “How would I have turned out if I’d lived in these conditions and seen no way out?” Now, it’s not an excuse because other people have also come from underprivileged backgrounds and managed to live a fairly decent life, but it must affect people, there’s no two ways about it.

Alcohol and drugs cause the bulk of murders, don’t they?

They cause the bulk of everything. Even the admissions to hospitals. The strain it puts on the health service is massive.

What about flashbacks and trauma – how do you cope with that?

I don’t get flashbacks, it doesn’t trouble me. If you get to that stage you should get out. Because it’s not going to get any better or easier [laughs]! I sleep easy at night.

On the crime scene, you always looked so glamorous: the red lippie, the heels. Was it part of your armour? Did the heels give you power?

I like wearing heels because I’m so small. Otherwise people won’t see me! When I started out in court in Glasgow you had to stand in the court box, and these things are built for men, and so the first time I went in you could just see my little head peeking up over, and I thought, “Okay from now the highest heels possible!” So yes, the heels are part of my persona as a forensic pathologist. Heels and lipstick – let’s go!

You say in the book that you wouldn’t have made a good doctor. Why?

It’s not that I didn’t have any empathy for patients, I just found it quite difficult. As I made my way through the specialities while training as a junior doctor, I was like, “No, I don’t want to do that” or “No, I’m not good enough to do that”! And then you’d see patients brought into A&E and they’d be writhing about in agony and I’d be looking around going, “Could someone please help this person?” But the person that should have been helping was me! I didn’t know what to do with them. I would have lost sleep if I had patients! I would have been in first thing in the morning going, “Did anyone die during the night?!”

At home then, do you like doing puzzles? Do you like games like, Escape Rooms? And if something goes missing, are you like, hmm… a clue?!

Yes! [laughs] The kids always give me puzzles for Christmas and my husband is standing there going, “What are you meant to do with this?” [laughs]

About your husband – you say he can get irritated about your cavalier attitude to your safety (in particular when you went to war torn Sierra Leone to work) – is there something in you that likes life on the edge?

I don’t think that far ahead. I just think “that sounds interesting” and off I go! I never think about the danger and I think that’s what galls my husband a bit. Because he’s there thinking she’ll be coming back in a box and I’ll be left to look after the children! I always just think it will all work out.

How has retirement worked out? For someone who worked tirelessly all her life, it must have been a bit of a shock to the system?

Everybody was saying I’d be demented with boredom so I made a plan and decided that I was going to treat the first year like a gap year. So we moved house, I wrote the book, and I decided I’d start getting fit and looking after myself. Coming towards the end of the year I thought, “Okay, I’ve had the gap year, what am I doing next year?” And then the pandemic hit! I was quite delighted! I must be the only person in the world who is quite delighted that we can’t go anywhere! There are two old dears living next to us who are in their 80s and they are obviously shielding and they’re saying to me, “Why are you shielding? You don’t need to!” And I’m like, “I know, I know, but I just think it’s best for everyone!”[laughs]

A total introvert then?

Absolutely, I’m not the life and soul of the party! All I’ve ever done is talk about work and so I’ve had to learn a new language because if you meet a wee wifey in Tesco you can’t turn around and go, “Did you see about that death the other day?!” So I had to learn how to do small talk!

What about the husband then? Is he like you?

The opposite! He’s the guy out in the garden polishing the car looking to see who’s walking down the road and up for a chat! In his head he’s saying, “Please talk to me because she doesn’t say anything!” [roars laughing]

Who do the kids take after?

Well, Sarah is an assistant fashion buyer with River Island and my son Kieran is a lawyer with Arthur Cox. And no, I’ll never be a grandmother, because they’re just like me and don’t like kids either! [laughing again]

Yes, you say you don’t like children. You’re probably just feel awkward with children, no?!

No, I don’t like them! I just always feel uncomfortable with them.

But you didn’t feel uncomfortable with your own children, although we know that your husband did a lot of the parenting solo.

True. Even when my kids wanted to have friends home from school, I’d be like, “Really, do I have to feed them? Do I have to talk to them?!” And Halloween was always my worst nightmare!

Bet you loved your 2-weeks isolation here in Ireland in advance of this string of publicity?

I was delighted with myself! Having been stuck at home with my husband for the last six months it was great to get away! I just brought a load of books and read. What do I like to read? All the crime stuff!

INTERVIEW: Bianca Luykx

PHOTOGRAPHY: Lili Forberg; misslili.net

Shot on location at No. 25 Fitzwilliam Place, a beautiful venue for a romantic wedding reception, civil ceremony or civil partnership in the heart of Dublin City Centre. For an in-person or virtual viewing, contact mark@25fitzwilliamplace.ie, or for more information, see: 25fitzwilliamplace.ie.

Beyond The Tape: The Life and Many Deaths of a State Pathologist, by Dr Marie Cassidy, published by Hachette, priced at €15.99 is available nationwide.

Special thanks to Elaine Egan.